In myth, cats are said to have nine lives.

By his account, a Rockingham man, Edward Scipio (Sip) Hart, could perhaps claim to have had 14 “lives.”

He served for four years, two weeks and one day in the Army of the Confederacy.

During that service in the War Between the States, in between being held as a prisoner of war by Union troops, Hart said he was wounded 14 different times in battles and was shot 26 times in all with bullets.

He enlisted in the Pee Dee Guards on May 30, 1861, at the age of 28. Not known to be a robust young man, he was once turned down for life insurance. He died June 7, 1929, at age 96. He is buried at Northam Cemetery in Rockingham.

DETAILED AS COLOR GUARD

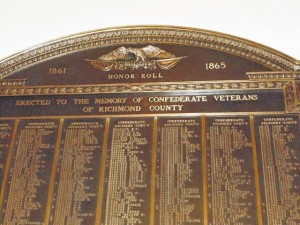

E.S. Hart’s name is listed on Confederate Veterans Honor Roll at the 1924 Richmond County Courthouse. He has an “X” beside his name for being wounded in action.

By May 10, 1862, Hart was promoted to full corporal and on May 20 was detailed as the Regimental Color Guard to carry the colors into battle.

He is among the few soldiers personally recognized for his bravery in the history, “North Carolina Troops, 1861-1865, Twenty-third Regiment.” He, of course, was a survivor when many such brave men lost their lives. Officers of the times commended most all men under their command for their bravery.

At the Battle for Spottsylvania (old spelling) Court House, Virginia, on May 14, 1864, it was said in that N.C. history that, “Our regiment, though small, contained many a gallant spirit, and many heroic deeds were done on that dark and dismal morn.

“E. S. (Scip.) Hart, the flag bearer of the Twenty-third, was especially brave; again and again rushing forward with the colors, which were never for a moment lowered except when Scip. was felled by a clubbed musket in the hands of a stalwart Yankee.” He was also captured along with others.

H. C. (Clay) Wall of Rockingham, then a sergeant with the Pee Dee Guards, after the war wrote a small book entitled, “Historical Sketch of the Pee Dee Guards.”

He later was one of the main authors of the chapter on the 23rd Regiment in the five-volume set about “North Carolina Troops.” As a representative in the N.C. General Assembly in 1899-1900, he was credited with getting the state to publish that work. He died before it was published.

In his book, Wall states: “Individual incidents, doubtless, are not lacking, only the facts and circumstances are not at hand to give preeminence for peculiar dash and gallantry in such a fearful emergency to some particular name or names, but to say that the Pee Dee Guards, as a company, were there (Spottsylvania) and participated in these critical attacks by which the Confederate line was restored and then successfully held against charge after charge of the most determined violence, is quite sufficient for the purposes of an historical sketch of their career.

“We would mention, nevertheless, that Corp’l E. S. Hart, of the Pee Dee Guards, was flag-bearer of the regiment (23rd N.C.) in this battle, as he had been in many previous engagements.

GALLANTRY IN ACTION

“His character for gallantry in action was proverbial among his comrades. In the hands of Hart, while he was able to be ‘on his pegs,’ that flag was never lowered….” until he was struck down and captured.

Other members of the Pee Dee Guard who were casualties in the battle were John Duncan, mortally wounded and died; W. C. Covington and J. C. Ussery, wounded; Thomas Pennell, mortally wounded and died; and Capt. A. T. Cole and Columbus Crouch were captured.

From the war until his death, Hart was known to recall at times his adventures as a soldier.

His name is cast in bronze with his comrades on the large plaque on the left side of the lobby in the 1924 Richmond County Courthouse. It was erected to the “Memory of Confederate Veterans of Richmond County.”

The honor roll lists all those veterans (1861-65) with marks beside their names for killed-in-action, died-of-wounds and wounded-in-action. There is an “X” beside Hart’s name for wounded in action.

Also included are the names of veterans of the Spanish American War, 1898-99. Listed are three “white” and 12 “colored.”

On the opposite wall of the lobby is an equally large bronze plaque “Erected in Memory of Veterans of World War of Richmond County,” from 1914 to 1918. In 1924, there had been only one world war.

The Pee Dee Guards took part in every major movement of the Army of Northern Virginia during the war.

Hart was beside Melville Holmes of Co. G, 23rd, when he was mortally wounded on reconnaissance within three miles of the U.S. Capitol building — the man to fall nearer the federal Capitol than any other Confederate.

The first two times Hart was captured, he was released in an exchange of prisoners with the Union Army. Such exchanges were soon discontinued by the Union Army when they realized Confederate prisoners were returning to the battlefield.

UNION PRISONER

He ended his service in a Union prison at Hilton Head, South Carolina, and then transferred from there to Fort Delaware in Delaware, Maryland. He was a prisoner of war from May 13, 1864, to March 12, 1865.

He took an oath of allegiance to the reunited United States of America on June 16, 1865.

At age 92, Hart was asked to accept the 1924 Richmond County Courthouse on behalf of Civil War veterans in dedication ceremonies in September 1924.

He was introduced by the sitting judge, Henry P. Lane, who said, “I was thrilled when I looked at this program and saw that there was a place reserved for one of that fast-disappearing band of men who composed the grandest army, in my opinion, that ever trod the Earth, and an army that was led by the greatest band of leaders that ever gave commands to patriots.

“There will be accepted on behalf of that band we love, that we adore, that we reverence and worship for their heroic deeds because they fought for what they knew was right — on behalf of the Confederate soldiers of Richmond County, I present to you, Mr. Sip Hart.”

This was 1924 and with Confederate veterans still living, feelings were still high concerning the war. In December 1925, Hart was one of only 27 Confederate veterans still living in the county receiving a state service pension of $77.50 a month. There were 34 Confederate widows receiving pensions of $50 a month. Pensions increased later over the years as the number of survivors decreased.

Hart said he was no speaker, comparing himself to the long-winded grand speeches made by others that day. So he just told of an experience he had in prison.

Hart began by saying “…if it (the war) had gone on until now, I would have been there yet. I served my country.” He said of the time, “Lord, not my will but Thine be done. If it is Thy will for me to return, let me return; but if I fall in the field of battle, let me go.”

He did fall, but lived instead.

CAT STEW

In prison at Hilton Head, he was living on “three little hard tacks (simple crackers) a day, not a drop of grease, not a grain of salt.”

One day he asked a guard to allow him to go out on an island and fish. When told he might run away, Hart said, “I have never run yet except to the front.” Trusting him, the guard took him and a friend to the island.

Coming back, he and the friend stopped by a Union soldier’s tent and negotiated to buy his cat. They paid $5 for it. It weighed 11 and one half pounds.

He said he turned to his friend and said, “Pete, we will have a dinner today.”

The Yank looked at him and questioned him, “You are not going to eat that cat,” to which he replied that he bought it to eat.

A wounded Confederate officer in prison, whom Hart had been looking after, gave them some flour to make a stew. “I made a kettle of three and one half gallons of cat stew, and I ate it.”

Hart ended his short dedication speech saying, “I have lived a long time for a man that was shot up in the War like I was. I was shot 26 times; I toted one bullet a long, long time.

“My son told me to let the doctor get it out, but I was not ready, and one day when I was feeling for the bullet, it fell to the floor. It is in my trunk now. I meant to bring it here today. I wish you all well.”

In an article in the Rockingham Post-Dispatch, April 26, 1928, when 95 years old, Hart was said to later wear a piece of that or another bullet as a watch fob that he said he removed himself from his side with a pocketknife given to him in 1861 by Confederate Capt. W. I. Everett of Rockingham. He had carried that knife for 50 years.

When Everett’s son, N.C. Secretary of State W.N. Everett, died in office in 1928, Hart walked from Pee Dee Village to Rockingham Methodist Church; and in respect, followed the funeral cortege on foot to the family cemetery on LeGrand Street. Sixteen months later, Hart died at age 96. He is buried at Northam Cemetery, north of Rockingham.

LIQUOR FROM GEN. GRANT

He was fond of telling one tale involving Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. In one battle before capture, he was wounded; and a rapid retreat of Confederate troops left him in the enemy’s hands.

He would say that he was badly shot through a leg, and he was lying on the ground when Gen. Grant rode up on his horse.

“Give Johnny (Rebel) a big drink and and dress his wound,” he said the general commanded. It was done. Then Grant commanded, “Now give him another swallow and another.” Hart called it “likker,” and said it was Scotch whiskey.

Hart said, “That was the nearest I ever came to getting drunk, and U.S. Grant did it.”

The 1928 newspaper article said the injury took place the day before the surrender of the Confederate Army at Appomattox. Hart had been freed from federal prison March 12, 1865. The surrender took place on April 9, 1865. That would mean he had rejoined his Confederate Army unit for the Battle at Appomattox after being released from prison.

That seems true to Hart who told the Union prison guard earlier that: “I have never run yet except to the front.”

When he returned home, Hart married Sarah C. Sedberry on Sept. 14, 1865. They had nine children. Of the eight who survived to become adults, they produced more than 50 grandchildren, and a dozen or more great-grandchildren in 1928. By then, he had stopped counting his descendants, saying, “they are getting to be as the sands of the sea.”

For his service, he is now a part of Richmond County history, if not folklore

By: Tom MacCallum